A Trifurcated

2014 WHITNEY BIENNIAL

Bids Farewell to its Madison Avenue Home

WRITTEN BY Kitty Garner

Read the full post to discover more about the 2014 Whitney Biennial!

“Its architecture is like a horror movie” wrote one particularly caustic critic, referring to the Marcel Breuer building which has housed the Whitney Museum of American Art for nearly half a century. “Stygian”, “menacing”, “bellicose”, “somber”, and “ornery” are some other choice words architecture critics have used to describe the structure. It has also been likened to a “three-tiered upside-down cake”. Yet many academics and other fans of Brutalist architecture championed the rather austere nature of the building and it certainly opened to much fanfare in 1966, with a celebrity A-list attending the ribbon-cutting including board member Jacqueline Kennedy. Indeed it was in this spare domicile that the Whitney Biennial was born in 1973. The 2014 show will be the final Biennial in the Breuer building as the Whitney decamps to its new Renzo Piano-designed home in the Meatpacking District next year, perhaps more suitable terroir for a contemporary museum than the buttoned-up upper east side.

Fittingly, there is a piece in this year’s Biennial which serves as an homage of sorts to the Breuer ziggurat. On the fourth floor, in a large windowed gallery, Zoe Leonard has created a capacious camera obscura using the museum’s signature trapezoidal window with its panorama of tony Madison Avenue as a prismatic lens. The window is covered save for a small hole which inverts the exterior scene and casts the image of the up-ended tableau onto the opposing wall of the gallery. One enters the dim space as the streetscape is projected on its head with traffic racing across the gallery ceiling, shoppers madly rushing topsy-turvy, and rooftops of brownstones skimming the floor.

While Leonard’s piece, cleverly titled 945 Madison Avenue, nods to the Whitney’s past, another work in the show, Artists Monument by Tony Tasset, looks to the museum’s future. The monumental sculpture is off-site on West 17th Street in Hudson

River Park, cunningly placed just steps from the Whitney’s new home. Like a sculptural hybrid of Gerard Richter’s 4900 Colors and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the piece is a massive color block of tiles engraved with the names of 392,486 artists culled from the past two centuries—those included range from the obvious to the obscure. The artist commented that the piece is about removing hierarchy as each artist has the same billing on the piece. A bit ironic, as the work itself was selected for a curated show, but nonetheless it is refreshing that this rather democratic piece was chosen as, perhaps, a harbinger of things to come.

Certainly there are pieces in this show which would bewilder Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney were she roaming the galleries of her museum today.

945 Madison Avenue and Artists Monument are two of the more successful pieces in this year’s Whitney Biennial, a show which, every other year, presents a curated snapshot of the state of contemporary art in America. When the Whitney first came up with this concept in the thirties, the task was not nearly as fraught as it is today and the museum boldly hosted a Whitney Annual. However, the post-Warhol era witnessed the death of art as it had been known and its resurrection took a form which would not be recognizable to former generations. Certainly there are pieces in this show which would bewilder Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney were she roaming the galleries of her museum today, including Peter Schuyff’s carved pencils, Lisa Auerbach’s knitted sweaters with political invective trim, and

The Bjarne Melgaard Room which could easily serve as the set of a seventies porn film with its plush velour sofas, kitschy pillows and silicone sex mannequins.

With no boundaries for the definition of art, the notion of presenting a comprehensive survey became pure folly. Whether by coincidence or not, it was at this time, in the early seventies, that the Whitney defaulted to an every-other-year format. It is absolutely axiomatic that whatever approach the Biennial takes is doomed to fail in the eyes of many due to the sheer impossibility of the task at hand and the countless art world panderers lobbying for representation of their special interests in the show. The breather year was perhaps necessary in order for the Whitney to process the vitriol each Biennial inevitably inspires. Truly, it has become the show people love to hate.

Since the notion of placing some sort of all-encompassing armature around contemporary art today is patently preposterous, the best the Whitney can do is come up with some sort of organizing theme that resonates with the current state of the art world. The Sao Paulo 2012 Biennial did a brilliant job by framing its show around poetics and the 2012 Whitney Biennial was critically acclaimed for presenting the hybridization of art. This year’s show could have leveraged any socially-relevant theme as a springboard but instead, the Whitney opted for a maximal approach.

variable. Private collection.; Lisa Anne Auerbach, We Are All Pussy Riot, We Are All Pussy Galore, 2013 (sweater). Collection of the artist; courtesy Gavlak Gallery, Palm Beach.; Photo via Andrew M. Goldstein, editor-in-chief of Artspace Magazine, from his article entitled “The Most Spectacular Artworks in the Whitney Biennial”.

The museum brought in three “outsider” curators to present three autonomous shows on three different floors. The concept is a bit absurd, particularly in a museum with admitted space constraints. The result is a show stretched too thin, wandering in too many directions, with sprouts of sheer genius that wither on a vine of inane inscrutability, tedious ephemera and derivative concepts. Still…go to the show! The good pieces are really good, and the entire experience makes one pause and take stock, an estimable exercise in our non-stop, never-look-back world.

The curatorial trifecta is comprised of Anthony Elms, a curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia and editor of White Walls; Stuart Comer, the media and performance curator at the Museum of Modern Art (formerly at the Tate Modern); and Michelle Grabner, an artist and a professor of painting at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Yale.

silk, 204 × 48 × 48 in. Collection of the artist; courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

Mr. Elms show is on the second floor and is the most academic—conceptually rich, albeit aesthetically challenged. A signature piece in his show displays an album revolving on a turntable, and yet no sound is emitted. At first blush one might think this is some sort of riff on John Cage’s 4’33” but upon listening more closely there is indeed some sort of sound—swirling air? The recently deceased artist, Matt Hanner, was part of the Academy Records collective and lived directly under Chicago airspace. He recorded the melancholy silence on September 11 and 12, 2001 when flights were grounded.

Mr. Comer’s selections are laid out on the third floor and the focus here appears to be works which reflect transition and flux. Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst’s Relationship series (2008–13) records the trajectory of this transgender couple’s involvement and their individual transitions, Drucker from male to female, Ernest from female to male. The forty-six chromogenic prints reveal angst, stoicism, and an alchemical intimacy—all displayed palpably.

Ms. Grabner’s fourth floor is the most buoyant and energized, and surely would have floated to the top had it been installed on a lower floor. It is also jam-packed, containing roughly half of this very cramped Biennial’s works. Craft, expressionist painting, and bulbous sculpture make for a madcap top floor. A memorable work from Ms. Grabner’s selection, Pillar of Inquiry/Supple Column, is by octogenarian Sheila Hicks. Masses of rainbow colored string seem to pour out of the ceiling, cascading onto the floor in an ebullient fiber sculpture.

Although each curator has chosen some memorable pieces and there is a laudable void of trophy art on display, the selected works are uneven and the totality of the experience leaves one wanting. Too many of the pieces cannot stand alone—they require the crutch of a verbose wall panel. This is fine to a degree, as conceptual pieces in particular can require a bit of work. But here, principally on floors two and three, one spends more time reading than looking. In general it feels as if the three curators are playing tug of war with us—pulling us hither and yon.

One could simmer and whine about the fatuity of organizing the Biennial in this hat trick fashion or one can just roll with it…truly this seems to be the manner in which most Whitney Biennials are enjoyed…cede a definitive understanding of the whole and instead focus on individual pieces which are intriguing and the trends and themes which support such works. Employing this thematic rubric to dissect this year’s Biennial, there are several themes which emerge…

SOUNDING OUT SOUND

Performance, video, and sound installations—time-based art forms—are ubiquitous in this year’s Biennial but let’s just focus on sound. Entering the show, one is greeted by Ambient Marcel (Waiting, Working, Erupting), a piece by Sergei Tcherepnin which employs surface transducers to make several of the distinctive Breuer lobby light fixtures emit sound. The lights click, clack, and squeal creating a disturbing mood as one prepares to enter the show. The odd utterances from above make the patrons pause and actively listen in a futile attempt to make sense of the noises, and the quotidian, perfunctory lobby space is transformed into a gallery. And if one becomes impatient with the notoriously slow elevators and opts for the stairs, Charlemagne Palestine has a surprise waiting for those with sturdy quadriceps. Not to spoil the fun but stuffed animals, fabric, speakers, and resonant concrete combine for a hypnotic stairwell frenzy. “I’ve been coming to the museum since it was built, and I’ve always loved the staircase,” said the artist. “This particular kind of concrete has a fantastic resonance. It’s Taj Mahal-esque.”

THE CULT OF THE DEAD

(detail). Twelve-channel sound installation. Collection of the artist.

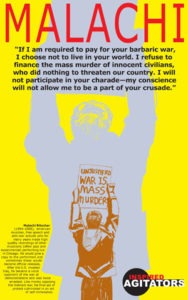

Perhaps it is a bit morbid to note but ghosts of dead artists haunt this year’s Biennial. The painter Richard Hawkins and the photographer Catherine Opie have organized a remembrance of their art school classmate Tony Greene, who died of AIDS at thirty-five. Greene painted sensual patterns on tinted photographs of animals and male bodies. There is also a piece displaying the ephemera of the flamboyant and lascivious art critic Gregory Battock who was murdered in 1980 and yet another work on documentarian Malachi Ritscher who died of self-immolation in protest of the Iraq War in 2006. And we are just getting started…this Biennial has turned the Whitney into a veritable morgue.

PAPER AND ARCHIVAL OBSESSIONS

There appears to be an almost fetish-like obsession with paper and archives this year. Mr. Comer attempted to explain the appeal, “Now that we have access to more archival material, we are all preoccupied with how we can reanimate it and create living histories.” Often archival-based works simply present an organized mass of archival material as content, and it appears this curatorial misstep is evident in duo Valerie Snobeck and Catherine Sullivan’s installation based on a Chicago anthropologist’s obsession with airline menus. However, the archival based work by Public Collectors on the aforementioned Malachi Richter is riveting. Semiotext(e), the independent publisher for theory-infatuated intelligentsia, is presenting a series of small books for the Biennial. Foucault, anyone? Also on view are the vitrined spiral notebooks writer David Foster Wallace (whose 2008 suicide also casts him with the Cult of the Dead above) kept while working on his unfinished novel “The Pale King”.

Literary Trust.

WOMEN, REALLY?

Although still less than a third of the works in this year’s Biennial are by women, there is much more gender equality now than in years past. The Guerrilla Girls would not be content but they would admit to seeing the fruits of their labors. Ms. Grabner explained her interest in female artists, “I am focusing on a handful of women artists who take on the authoity of abstract painting — its history, its ambition, and its relationship to power and gender. I wanted to put them together to underscore how different the language of abstract painting can be.”

But at the Brucennial down in the Meatpacking District, women have quite literally stolen the show. This is the last Brucennial, the non-curated, alter-ego of the Whitney Biennial that has run concurrently with the last three Biennials. Organized by the Bruce High Quality Foundation and Vito Shnabel, the art-dealing son of Julian Shnabel, this year’s Brucennial is showing only works by women.

COLLECTING COLLECTIVES

Thirty-eight poets, musicians, thespians, writers, and visual artists from across the globe form Yams—shorthand for HowDoYouSayYamInAfrican? The members are mostly black and mostly queer, by their own admission. They have come together in New York to collaborate on their contribution to the Biennial, a filmed opera—spoken, sung, chanted—which reveals how the specter of race haunts black identity. There are eight collectives in this year’s Biennial. They all reflect the challenges inherent in collaboration and reveal the manner in which our increasingly virtual and interconnected world is changing the way collectives work. It was in the eighties that collectives made their Biennial debut, and at that time they were primarily ideological and dogmatic. Today, the internet and social media allow remote collaboration and there is liberal cross-over between artistic disciplines. Ms. Grabner commented that “collectives in the past performed a critical role that poked at art world hierarchies and its cult of the individual genius but they function differently today…They reflect the proficiency of our networked culture. Authorship has become very slippery and the ownership of ideas has become less interesting today than the rapid sharing of them.”

by hanging bead sculptures by Sienna Shields. Photo: Karsten Moran for The New York Times.

Other thought-provoking themes emerge as well, and there is some rollicking fun to be had at this show (despite the tiresome wall panels), but the whole of the 2014 Biennial is less than the sum of its parts. As Mr. Elms observed in his curatorial statement, “Assembling an overview of American art these days is a fool’s errand.” Right he is. And yet some attempts are more successful than others. This show was perhaps just too ambitious for its own good. Still, it is laudable that the Whitney continues to try, despite being slapped in the face by dismissive and rancorous critics every other year.

Like many, I am already eagerly conjuring the 2016 Biennial in the Renzo Piano space but at the same time I find myself a bit verklempt in imagining a Biennial not in the Breuer building. It is time for the move, yes, as the Whitney outgrew the space decades ago. And yet, it is indeed bittersweet to say farewell to the only place any of us have ever seen a Whitney Biennial. But no need to get too saccharin, as Thomas P. Campbell and Co. have come to the rescue…the Met will open a modern and contemporary offshoot in the Breuer building once the Whitney move is complete. No, it won’t be the same but at least the building will still serve its intended purpose, instead of morphing into a Uniqlo or an H&M. Marcel Breuer would most likely be well-pleased with the next chapter in the life of his Brutalist masterwork, and we get to have our (“three-tiered upside-down”) cake and eat it too.

The Whitney Biennial 2014 runs through May 25th. For more information and to purchase tickets, visit whitney.org.

Leave a Reply