a review of Beth Macy’s Factory Man

WRITTEN BY Kitty Garner

A dark, menacing tempest taunted the southern foothills of Virginia on the night of October 18, 1937. The storm swirled and pitched through the gaps and hollows of the Blue Ridge, and then, as if it had found its mark, hovered and settled over the tiny hamlet of Bassett, Virginia and unleashed its fury—a relentless torrent of rain. The Smith River swelled, crested its banks and rose until its waters rushed across the floors of Mr. J.D. Bassett’s cavernous furniture factories, threatening to ruin not only his company, but his eponymous town as well.

A dark, menacing tempest taunted the southern foothills of Virginia on the night of October 18, 1937. The storm swirled and pitched through the gaps and hollows of the Blue Ridge, and then, as if it had found its mark, hovered and settled over the tiny hamlet of Bassett, Virginia and unleashed its fury—a relentless torrent of rain. The Smith River swelled, crested its banks and rose until its waters rushed across the floors of Mr. J.D. Bassett’s cavernous furniture factories, threatening to ruin not only his company, but his eponymous town as well.

Ironically, there was reason for jubilation in the midst of the deluge, for Mr. J.D.’s first grandson was born that same day, and the family furniture dynasty finally had its long-awaited male heir, John D. Bassett III (“JBIII”). From the moment of his birth, the destiny of the third generation scion to the Bassett furniture fortune seemed preordained, as laid out in an exultant letter Mr. J.D. wrote to his infant namesake that very night, just as the floodwaters mounted and threatened to destroy the very legacy he wished to bestow upon his grandson. Decades later, when family loyalties shifted and JBIII was stripped of his birthright and left Bassett for good, locals said that the flooding of the town the night of his birth was a prescient sign that the heir would be pushed out of Bassett, as surely as if the infant had been caught in the frigid rapids of the Smith River that stormy Depression-era night.

The flood scene described above is recounted in Beth Macy’s enthralling new book, Factory Man, and the storm might be considered, in literary parlance, an example of pathetic fallacy, a term coined by John Ruskin to describe the manner in which writers attribute human qualities to inanimate objects of nature in order to give atmospheric nuance to their works. Surely Macy must be employing this and sundry other literary devices, for how else could she craft a tale so fanciful? And yet her book is a biography not a novel, and is built upon facts, not metaphors. Factory Man is the product of years of painstaking research, and the flood, as well as the hurricane and the manifold infernos which are also described in the book, were not conjured by the author to heighten the tableau she presents. Rather incredibly, they are events which actually occurred and defined the life of John D. Bassett III.

Nor did the author contrive the stranger-than-fiction tales of feudal infighting, dynastic power struggles, miscegenation, grave-robbing, corporate incest, Machiavellian trade maneuvers, Chinese robber barons and K Street political intrigue which are relayed in the book. Macy takes the fodder of JBIII’s life and weaves a tale that is positively Shakespearean in its sheer drama. The story stretches from the foothills of Appalachia to burgeoning factories in rural China, from congressional back rooms to ex-pat enclaves in Indonesia. It spans a long and steady century of ascension, as Bassett Furniture Industries became the largest manufacturer of wood furniture in the world. And it relays how quickly the “waltz of cheap labor” lured Bassett and almost all other furniture manufacturers to sign on to the “dance card” of the Chinese, shuttering their domestic plants, abandoning manufacturing and becoming importers and retailers. Left in their wake as wallflowers were legions of unemployed, unskilled factory workers and entire company towns reeling in desperation.

After describing the ascent of Bassett under the patriarchy of Mr. J.D., Macy reveals how JBIII was groomed to take the reins of his family company and then, in a stunning and unforeseen reversal, was forced to relinquish what had seemed inevitable. Growing up in a town where all was controlled by his family—the bank, hospital, schools, churches, even the electricity bill all bore the Bassett moniker—the brash JBIII surely was born with a silver spoon in his mouth. Yet that silver spoon would tarnish and it would be the sweat of his own brow, not the sway of his surname, that would bring back its luster.

After graduating from Washington and Lee, JBIII shocked everyone in Bassett by joining the army. The young lieutenant learned what real leadership was as he patrolled the East German border. He also found time to chase winsome fräuleins from behind the wheel of his Porsche roadster. JBIII returned home to find his three-year tour of duty had allowed his brilliant albeit opportunistic brother-in-law to insinuate himself into the family power structure and ultimately gain control of the company. JBIII was forced to prove his bonafides at Bassett over and over, but to no avail. He succeeded even when his assignments were Sisyphean yet his victories were Pyrrhic. He had been summarily shut out.

JBIII finally saw the writing on the wall and left Bassett, both the company and the town, in 1982 to build up a much smaller company, Vaughan-Bassett, in Galax, Virginia. This concern was the family company of his wife, who also happened to be his fourth cousin. To add yet another gothic layer to the veneer of this improbable tale, Vaughan-Bassett was founded with seed money from none other than Mr. J.D., thus being a corporate “kissing cousin” of Bassett. At Vaughan-Bassett, JBIII’s story became one of David and Goliath, where he was perpetually cast as David and the role of Goliath morphed from his domestic competitors to the much more formidable Chinese. Macy shows us how the Churchill-quoting JBIII leveraged all he learned in the army and from his grandfather to help him develop a strategy to compete. She reveals how the entitled boy—who had partied his way through W&L with his tandem team of rowdy frat brothers, kegs-ontap and girls in cashmere twin-sets—became a driven man working 14-hour days whose sole focus was saving his factories and the jobs of those for whom he felt responsible.

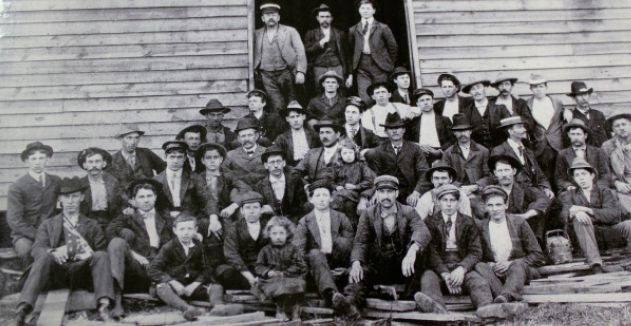

Historical Center.

JBIII’s strategies at Vaughan-Bassett were practical, and they produced results. He kept his bank account fat and his factories lean, investing in cuttingedge five axis routers and luring the best talent. He warehoused increased inventory so that he could implement and market an express shipping program that the Chinese could not rival. He went without a salary when needed, infused millions of his own equity into the enterprise and worked harder and longer than anyone. Most significantly, he bolstered his workers and made them believe in themselves and their ability to innovate and compete. He backed up his words with actions, canvassing them for suggestions on improving operations, offering creative incentives, doing any and everything to prevent lay-offs and providing a free on-site medical clinic not only for the workers, but for their families as well. He kept his sense of humor, even when he could not sleep at night, and took solace in his quite remarkable wife, his lively children, his loyal bird dogs and the ever-present notion that he was doing the right thing.

As a result Vaughan-Bassett was able to play ball with the Chinese until it became apparent that the game was being played on a field that was increasingly uneven. JBIII was neither a xenophobe nor a protectionist, and he had a pugilistic bent, relishing a good fight, but he wanted the battle to be fair. With the arrival of the Dalian dresser, JBIII knew he was up against a pernicious opponent bigger even than his own gumption. The dresser was a Chinese knock-off of a Vaughan Bassett piece which cost $235 to make in Galax. The Chinese were wholesaling it for $100. JBIII knew the government-subsidized firms in China were selling products in the U.S. for less than they cost to produce in China—“dumping” in a brazen attempt to do nothing less than destroy American furniture manufacturing.

JBIII had his hackles up now, retreat was not an option, and he took on a range of roles in order to combat this lethal and very present threat. He became a first rate sleuth, traveling to China in the guise of an importer, as he, his son Wyatt and a Taiwanese liaison named Rose sniffed out the remote production facility for the Dalian dresser near the North Korean border. He also became well-versed in esoteric trade law and, with the help of handsomely paid King & Spalding lawyers, discovered the legal redress for dumping: the Tariff Act of 1930 and the godsend Byrd Amendment, which put the duties awarded not in the U.S. Treasury but in the coffers of the injured companies.

Still Making It In America, a co-production of The Roanoke Times and Equal Voice News. Video by Ryan Loew.

Perhaps the most remarkable role JBIII took on was as a charismatic industry organizer who had an uncanny ability to mobilize a fractured cartel and lead one of the largest anti-dumping campaigns ever waged against China. It turns out JBIII was a born general who, had he been reared a generation earlier, just may have given Patton a run for his stars. His fervent leadership is all the more remarkable when one considers the fraught milieu in which he was operating, as garnering the troops proved much more exacting than one might think. He needed to have 51 percent of his industry sign the petition, and yet many of those he was soliciting had already closed their plants and become importers and

thus were actually benefiting from the dumping discounts, as were the retailers who were JBIII’s customers. Many vilified him for bringing the petition and numerous former customers boycotted Vaughan-Bassett products. Nonetheless, he marched up to Washington with the requisite 51 percent, bivouacked at the Commerce Department and led a triumphant campaign. Had the petition been brought a decade earlier, before his peers had abandoned their factories, perhaps American furniture manufacturing could have survived. Instead, a good deal of production shifted from China to Indonesia, and most petitioners used their awards not to restore American manufacturing, but rather to expand their retail and import operations.

Still, JBIII did save his own factories and, in turn, jobs for hundreds of workers. He used his awards to further improve his plants, raise wages, purchase more high-tech equipment and reopen a long-closed factory in Galax. While the turncoat higher-ups in his industry may have pilloried JBIII, his factory workers championed him and committed to work even harder. Vaughan-Bassett survived and is prepared to thrive as the housing market wakes from its derivative-induced coma. JBIII is quite literally the last man standing, producing furniture made 100% in America, and his persistent belief in and support of his workers saved not only his company but also the town of Galax.

Epic in scope and piercing in the myriad emotions it evokes, JBIII’s tale needed to plied by a writer keen in her craft, and Beth Macy delivered with Factory Man, proving she deserves her panoply of journalism awards. The tale leaves one perplexed by the naiveté and short-term vision of American manufacturers, galled by the unfettered ambition and nefarious tactics of the Chinese, frustrated by the costly, protracted and arcane legal route to equity, and incredulous at the vast underestimation of the moxie of the American factory worker. JBIII witnessed an entire industry withering on a once thriving vine that everyone in the corporate board rooms gave up for dead. But the “sawdust in his bones” told JBIII that the vine was still alive. He believed in American manufacturing and so did the displaced factory workers who would “crawl on their bellies like a snake if it meant they could bring it all back.”

Mr. J.D. wrote in his letter to his grandson in 1937 that he hoped he would do “big things,” and indeed he has, and Beth Macy has as well, in expertly telling the quite compelling and endlessly entertaining story of John D. Bassett III.

Leave a Reply